Joep Leerssen

Emeritus Professor, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, History, Maastricht University

Correspondence to Joep Leerssen, E-mail: leerssen@gmail.com

Volume 1, Number 1, Article ID 8, December 2024.

International Journal of Documentary Heritage 2024;1(1):8. https://doi.org/10.71278/IJODH.2024.1.1.8

Received on August 29, 2024, Revised on Novemver 20, 2024 , Accepted on December 05, 2024, Published on December 30, 2024.

Copyright © 2024 International Centre for Documentary Heritage under the auspices of UNESCO.

This is an Open Access article which is freely available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND) (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Discussions of cultural and literary canonicity usually extrapolate “historical importance” from applying axiological (ethical/aesthetic/pedagogical) value judgements to the available cultural heritage, including documentary heritage. As such they cloak their contemporary topicality in the discourse of historical importance, in the process eliding their own transience. This research looks at the documentation indicating historical importance. The documentation itself is a historically accumulated corpus, which provides one indicator to measure the rise and fall in “canonicity” of cultural figures over the decades and centuries. The chosen test case is that of Dutch literary and cultural history, as referred to in the holdings of the Netherlands Royal Library.

Canonicity, Nationalism, Filiation and Affiliation, Dutch Cultural Heritage

The fact that literary texts can be read in diverse legitimate and equivalent ways opens a new challenge to literary history which, as far as I know, has not yet been tackled. This would be to offer a history of readings of a certain literary text at a certain period or in different periods, and, connected to this, the history of the “life” of a literary text.

Roman Ingarden, 1935.1

The online Encyclopedia of Romantic Nationalism in Europe (Leerssen et al., 2020; henceforth ERNiE) contains many thousands of instances of “banal nationalism” (Billig, 1995): the assertion and celebration of national identity in popular literature and music, mass-reproduced imagery (e.g. banknotes and postage stamps) and public statues. This in turn documented the ties – diffuse but intense – between cultural canonicity and banal nationalism. The implication is that canonicity is maintained, not only as a high valorization of cultural heritage curated topdown, but also documented and perpetuated in its diffuse presence in everyday culture. That is what this article wants to explore, specifically by conducting a meta-analysis of Dutch cultural canonicity as measured against the holdings of the Netherlands Royal Library. Before we come to this meta-analysis of Dutch cultural canonicity, some preliminary explanations are in order.

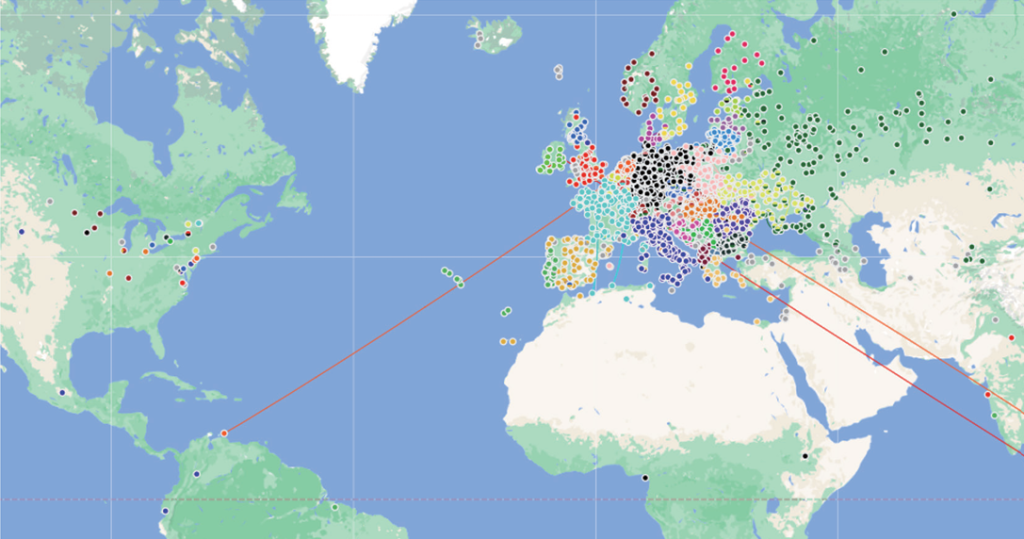

To illustrate the measurability of banal-nationalist canonical presences, a suitable example is provided by commemorative statues and monuments in public places. Such statues are, in fact, a corpus of historical documentation, albeit non-textual. Some 6500 specimens were collected and tagged for date of placement for the historical period and the cultural community to which the dedicatee belonged. This yielded the following geo-visualization (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Commemorative statues, color-coded for the cultural community to which the dedicatee belonged. Only statues to Europeans have been repertoried (US instances involved figures like Verdi, Shakespeare, Walter Scott, Leif Erikson). Lines represent the postcolonial removal of statues (Joan of Arc in Algeria, Queen Victoria moved from Dublin to Sydney). Interactively online at https://e-rn.ie/ monumentsinspace

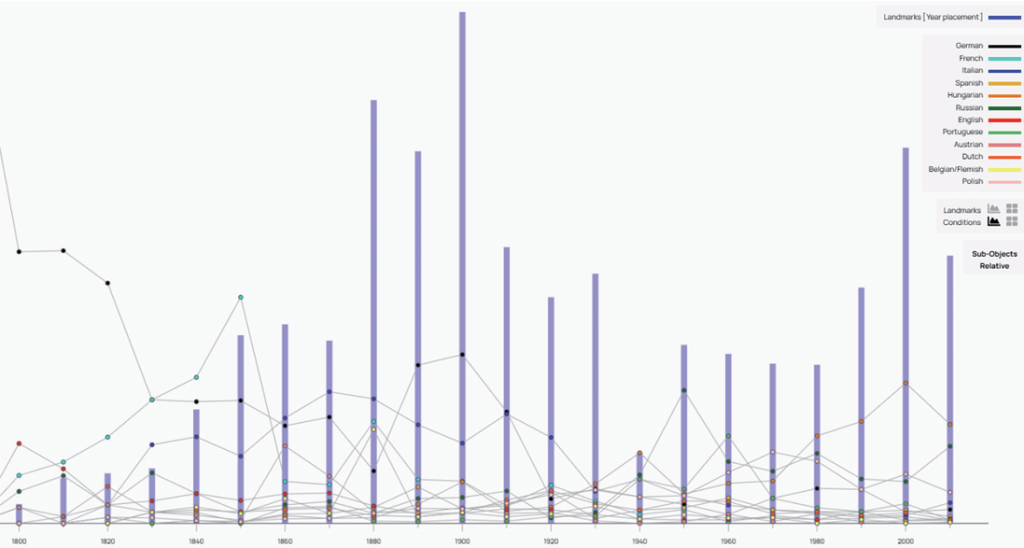

The marked congruence between the cultural background of the commemorated individual and the national territory of the state where these statues were placed is unsurprising (the state commemorates its own past and its own political or cultural heroes) but nonetheless meaningful, given the condensed period of placement (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Timeline of statue placements between 1800 and 2000. The bars indicate total production per decade, the lines the relative proportion of different nationalities. Pre-1920, the main productivity is West-European; post-1980, the main productivity is central- and East-European. Interactively accessible at https://e-rn.ie/monumentsintime

In an intense campaign, the public spaces of Europe were nationally branded, covered in a blanket of cultural-historical self-invocation, much of it retroactively recalling older figures from earlier centuries. These statues are not a sedimentation of European history left behind over the course of its long development, but the impact of a post-1800 agenda of European historicism. As these statues document, a national canon of iconic figures was constructed retroactively in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, retro-fitting the present by reaching back into the past. The geo-visualization of Figure 1 allows us to read the nationalization of Europe’s public spaces inductively – emerging from the documentary data – rather than deductively: not so much as the material illustration of a nationalist mental climate, but as a dataset documenting concrete initiatives and allowing us to extrapolate a shared preoccupation from them.

The charting of datable, concrete instances of “banal nationalism” yielded a canon of oftenmemorialized figures thematized in different platforms and media (film, banknotes, statues etcetera), consisting of a core cohort of c. 450 “nationally iconic figures”. The list ranges from prehistoric and/or legendary heroes and chieftains to 19th-century nation-building poets and intellectuals (Polish Adam Mickiewicz, Scottish/British Walter Scott, Catalan Jacint Verdaguer, etc.).2

What emerges from the documentary evidence here is nothing short of a European canon of celebrated national memory figures, demonstrating how these were represented across different social strata and between different countries. What does this suggest regarding the concept and use of national canons in European historical culture? Are national canons the end result of a centuries-long trajectory of cultural memory and literary reception, or are they, like those nineteenth-century statues, a way of “retrofitting” the present by reaching into the past? And how can we use available documentation to decide between those two possible types of tradition?

There are few statues pre-1800 to Shakespeare, Camões or Dante, or to historical figures like Rembrandt or the Dutch admiral De Ruyter; but their prestige and “canonicity” have a much longer pre-1800 track record. The edition of Shakespeare’s First Folio (1623) documents the high esteem in which he was held by near-contemporaries, as does Admiral De Ruyter’s highly ornate, state-sponsored tomb in Amsterdam (1677). History is replete with signs of how Great Men (and an occasional woman) were admired and cherished by their immediate posterity. I have in my possession an engraving by the painter Godfried Schalcken (c. 1660-1706) reverently depicting his teacher Gerard Dou (1613-1675), wearing a beret in the style of Dou’s own revered teacher Rembrandt (1607-1669) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Godfried Schalcken, portrait of Gerard Dou “praeceptorem suum” wearing a Rembrandtstyle beret, c. 1700 (author’s collection, gift from Rolf and Magda Loeber-Stouthamer)

What we see here is a painterly filiation: a tradition in which influence flows from the past masters to the later followers. It is “tradition” in the Latin root sense of the word: a handingon from earlier to later generations, much like succession in a royal line of descent. It is particularly strong in organized crafts and in small-scale communities with a high proportion of direct (unmediated, face-to-face) communication: noble families, municipalities, academies, universities, salons.4

But in the historicity of culture there is also another vector at work, one which works backwards in time – like those statues to medieval figures put up in the nineteenth century. An example would be the invocation of the first-century tribe of the Batavi, described by Tacitus as having waged a heroic uprising against Roman rule from their territory in the Rhine estuary. The Batavi had gone under in history, and Tacitus’s description of them did not come to light until the fifteenth century; but they were then adopted and “canonized” as their symbolical ancestors by the 17th-century Dutch, also inhabiting the Rhine estuary, and also engaged in a heroic uprising (this time against Spanish imperial overlordship). Under Dutch colonial rule the Javanese city of Jakarta was rebranded “Batavia’” and in the twentieth century, a Dutch bicycle brand was called “Batavus”. That “Batavian Myth” (van der Woud, 1998) does not involve any actual line of descent, but, to recall my earlier turn of phrase, a retro-fitting of the present by reaching back into the past.

That is also a tradition, but one which works backwards; it is “memory” rather than “history”. Following the seminal essay collection by Hobsbawm and Ranger (1983), it has often been referred to as an “invention of tradition”. By now this somewhat supercilious historiographical approach has given way to the broader concerns of the emerging discipline of Memory Studies, which have also inspired this article.5 I therefore prefer to call such “invented” traditions (like the Batavian Myth) a form of “affiliation”. Unlike filiation, affiliation is an act performed in the present identifying and appropriating inspiring figures from the past for contemporary purposes (often, as per Said, 1983, in lieu of a lacking filiation).

Filiation and affiliation: these are the heuristic poles between which canons take shape. To some extent canons involve centuries-old lines of filiation, to some extent they are the result of a present-day process of projecting our values back onto the past. It is as such that I want to take a closer look at them. Both processes, filiation and affiliation, have left their documentary evidence, and prima facie we can say that they have run in tandem, with a tendency for affiliation to become stronger as older cultural communities modernize into enlarged societies where face-to-face acquaintance networks are submerged in enlarged communication patterns relying on media. While filiation is a strong factor in crafts, disciplines and institutions, affiliation is the default value of the media-carried, public-sphere experience of culture. Putting up statues or naming institutions or prizes after canonical figures is one part of that evidence (on the affiliation side). Filiation is documented when younger cultural producers explicitly take inspiration from predecessors (as in the Schalcken engraving).

One thing that the ERNiE analysis shows is an unmistakable gravitational process: all of history gets condensed into a relatively small cohort of core figures. This concentration tallies with a central characteristic of the lieu de mémoire as already pointed out by Pierre Nora; such a “memory nexus” combines a great number of historical significations into a single symbol (Nora, 1997). Over time, canonical figures become multifunctional; they are important for a variety of reasons and symbolize a variety of meaningful things. Possibly this multifunctionality is a sedimentation of the various meanings they acquired for a succession of later generations (in line with Ingarden’s motto at the head of this article).

Canonicity in culture is something that is frequently evoked, often challenged, debated or disavowed, but never quite abandoned. The notion is very deep-rooted that certain cultural artefacts, or cultural memories, have a special and historically enduring collective importance, an inspirational or pedagogical value, and that they therefore deserve to be singled out and symbolically enshrined as such. The root meaning was religious: which prayers were so fundamental that they should be repeated literally and verbatim in every religious liturgy; which religious texts were agreed upon to form part of the officially recognized set of sacred scriptures. The canon was aimed to buttress fundamentally important cultural heirlooms so as to maintain them undamaged across the entropic forces of time.

In the modern world, the transgenerational maintenance of cultural heritage has been applied, first to a “literary canon” designating the “classical” texts which enjoy an importance beyond the changing fashions and tastes of the day. Subsequently, the notion has broadened to the “historical canon” of figures and events which have proved formative for modern society and whose remembrance should therefore be familiar to any literate member of society.

Canons are by nature conservative: aimed at preserving past heirlooms, defending them against erosion, safeguarding them from extinction. It is for that nature that the idea of canonicity has frequently come under attack in the last century, first from avant-gardist anti- traditionalists and post-1968, in the decades of anti-authoritarianism, when the generation of post-1945 baby-boomers came of age. Even so, the societal and educational invocation of a canon has continued unabated (cf. generally Guillory, 1993). Literary critics of exceptional standing have thrown their weight behind a canon which they had devised from works and authors with a “classic” status: Harold Bloom’s The Western Canon (Bloom, 1994) and Marcel Reich-Ranicki’s multi-volume anthology Der Kanon (Reich-Ranicki, 2006). Both Bloom (born in 1930) and Reich-Ranicki (born in 1920) came in for criticism, mainly from a younger generation of critics who wished to apply a more progressive (Marxist, feminist or postcolonial) frame to the reading of literature. Bloom and Reich-Ranicki were chided most of all for their judgementalism. However, judgement was the name of the game for all parties involved: value judgements and an axiology of how ethics interact with aesthetics are common to both the canon-wielders and the canon-critics. Critical discourse is almost by definition axiological: imbued with value judgements (appreciation or disappreciation) either of an aesthetic or a moral-ethical nature. In recent decades, the value of inclusivity has become increasingly important.

Literary canons, valorizations and debates have also played themselves out in the Netherlands – with added complexity because “Dutch” culture and “Flemish” culture make use of the same literary language but take shape in two different societies/states: the Netherlands (rooted in the former United Provinces) and Belgium (rooted in the former Spanish/Austrian Netherlands). Processes of convergence and divergence between the “Dutch” and “Flemish” branches of Netherlandic-language culture have created a complex dynamic over the past centuries, which also affects canonization processes. A Canon of Dutch Literature was put forward by the Society for Netherlands Literature (Maatschappij der Nederlandse Letterkunde) in 2002, based on the preferences of its prestigious and self-selecting membership. A critical discussion of this, with an educational handbook, was brought out by Duyvendak and Pieterse (2007). In a characteristic process of repeated revisions-and-updates, fresh literary canons, in the form of commented anthologies, were published in 2015 and then in 2022 under the auspices of the Royal Flemish Academy of Language and Literature (Van Deinsen et al., 2022), partly based on opinion polls. These latter testify to an important underlying mechanism in canon formation: the recycling of texts in anthologies.7

In addition to the ethical and aesthetic value judgements embedded in the modern notion of canonicity, there are also sociopolitical ones. Cultural literacy is seen as an important force for social cohesion, establishing the common frame of reference which facilitates communication and understanding, and which provides a sense of common culture, between fellow-members of society. Using the language of memory studies, we might say that a shared canon creates a “mnemonic community” (Zerubavel, 1996), a group of people held together by a communally shared set of memories; and it is the nation that has arguably become the most prominent type of “mnemonic community”. The canon is an important pedagogical tool for the nationstate, informing educational strategies on how to socialize new generations and induct them into the nation’s mnemonic community. Policy makers and public intellectuals at the nationalconservative end of the political spectrum periodically issued calls to reinvigorate a traditional, nation-centered canon in public education.

In the Netherlands, a government-initiated National Canon had already been drawn up in 2006, primarily for educational purposes (cf. de Vos, 2009). It had been preceded by a Kulturkanon of the Danish cultural heritage (drawn up in 2004, when Denmark was under a nationalconservative government); Flanders followed suit in 2021. Although academics were involved in the canons’ elaboration, many professional historians voiced reservations (alternative canons were drawn up in Denmark; for Flanders, cf. Tollebeek et al., 2022; but also, Smets et al., 2023). A wider taste for national historicism was noticeable in the field of consumer culture recycling and publicizing the great moments and figures of the national past.8 In Denmark, the Netherlands and Flanders (the three countries that had defined national canons), there were television series (Historien om Danmark, 2017; Het verhaal van Nederland, 2022; Het verhaal van Vlaanderen; 2023) with explicitly national-narrative titles and, in Flanders, a nationalistconservative politician endorsing “the logic of promoting Flemish identity” (Abbeloos, 2023). Public and commercial media like cinema, television and musicals have since 2000 continued to recycle canonical national figures; witness the quiz election shows on “the nation’s greatest figure in history” – “100 Greatest Britons” (UK, 2002); “Die größten Deutschen” (Germany/ZDF, 2003) ; Suuret suomalaiset” (Finland 2004); “De grootste Nederlander” (Netherlands, 2004); “Os grandes portugueses″ (Portugal, 2007); “Megali Ellines” (Greece, 2009); “Il più grande italiano di tutti i tempi″ (Italy, 2010). Canons are everywhere, and by now the acronym GOAT (“Greatest Of All Time”) has become a widely-used commonplace.

Ironically, given their claims to identify cultural objects with a transhistorically lasting value, canons themselves seem to have a short shelf-life. A few years after they are announced amidst fanfare and controversy, they seem to stand in need of an update, or a recalibration. Harold Bloom and Marcel Reich-Ranicki have become half-remembered pundits of yesteryear. We have noted the ongoing updatings and retrofittings of the Netherlandic-language literary canon; the Dutch historical canon of 2006 was also revised and re-calibrated in 2020. That new version was adjusted to the fact that political sensibilities vis-à-vis the past had significantly changed in the intervening 15 years (Lavèn, 2020). Those 15 years stand in stark contrast to the many centuries that the canon itself is designed to enshrine.

Canons by definition are ambitemporal: they are used and debated in the present, and they reach back to a sense of historical permanence (greatest “in History”, “di tutti tempi“, G“OAT”). The discussions around the launch of a canon usually involve a contrastive juxtaposition (“What, if any, is the value of the old thing/person/memory in the contemporary world?”). But the affiliative vector (“this is what we nowadays, looking back in history, can take inspiration from; this is what belongs to us”) tends to be overshadowed by a rhetoric implying that the canon, even for a widespread public, is deep down a filiation: “this is how the greatness of our past has survived the intervening centuries to inspire us in the present; this is what we belong to”.

This aprioristic tendency to present a canon in the modality of filiation is problematic. Canonicity is a lieu de mémoire, a memory that has been reworked and reshaped and reselected in the light of later concerns, and such lieux de mémoire typically morph over time in response to the changeable needs of a shifting “present”. But the shifting, ephemeral, selfobsolescing nature of the present which affiliates itself to a canonical past is downplayed: each canon replaces its predecessor and consigns it to oblivion. How canonicity, as an ongoing, dynamic process, moves through time, how it performs an ongoing reconfiguration upon the remembered past, is an important factor in cultural history, and it is elided by canons’ built-in ambitemporality, asserting historical permanence by giving a mere snapshot of the relationship between timelessesness (then) and topicality (now). The Dutch national canon is accessible online under the URL entoen.nu, which translates as “andthen.now”.

The threadbare, iterative rounds of discussion about the usefulness (or not) of canons is itself part of this self-obsolescent self-renewal. I do not intend this article as yet another instalment in this cycle of canons-and-critiques, but intend rather to lift the discussion of canonicity – an intrinsic aspect of cultural memory, with its filiative and affiliative links to the past, and with undeniable pedagogical implications (van Oostrom, 2007) – out of the axiology of value judgements, and to conduct a data-based meta-analysis of canonicity. This meta-analysis consists of harvesting existing “canonicity indicators” as these were deposited over the centuries in a long-term repository like the Netherlands Royal Library, and charting, chronologically, how these indicators document, over the years and centuries, the rise and fall in canonicity of certain cultural heirlooms.

Literary historians have long been habituated to the idea that canons change along with the shifting values of succeeding generations.9 A canonical work does not just enjoy that status by standing on the shelf and being frequently picked up by appreciative readers; for it to be, and to remain, canonical, it needs to be reprinted, anthologized, recycled, adapted. This is what Ingarden (1935) and Rigney (Brillenburg Wurth & Rigney, 2011) call the “life of texts”. The place to encounter signs of that life, both filiative and affiliative, is, obviously, a library.

Focusing on the specific case of the Dutch national canon, a pilot probe was developed in 2017-2018 on the basis of the ERNiE technology at the Netherlands Royal Library (Koninklijke Bibliotheek) in The Hague (hereinafter KB). A national repository with a long history and rich documentary heritage from many centuries, the KB may be safely assumed to hold practically all relevant published materials in and concerning Dutch culture since the sixteenth century, with its database (underlying the KB’s catalogues) containing all relevant data documenting the Dutch afterlife of the country’s historical moments and figures.

On the basis of the ERNiE experiences, it was decided to use the documentation of the KB catalogue and its tagged metadata in order to provide a diachronic “citation index” establishing the “h-index” or “impact factor” of Dutch national-historical themes and figures over the years.10 One specific research question at the time was whether the Dutch cultural canon had experienced noticeable patterns of discontinuity, instances of decline or increase, particularly around the year 1800 (which in ERNiE had proved to be a tipping point).

An initial selection was made with the help of the N-gram Viewer of the Digital Library of Netherlandic Literature (Digitale Bibliotheek voor de Nederlandse Letteren, DBNL, hosted by the KB). The names of a number of prominent historical figures were run through the N-gram Viewer, which allowed us to see the number of textual references made to them from a wide selection of publications (including periodicals). This provided a good prima facie indicator of a figure’s filiative afterlife: the attention paid to him or her within subsequent literary productivity.11

KB librarian Juliette Lonij devised an export script for extracting the relevant catalogue data for use in the NODEGOAT data-management environment (the technology that also powered ERNiE; nodegoat.net); NODEGOAT developers Pim van Bree and Geert Kessels curated the ingestion of these data in NODEGOAT. All in all almost 17,000 items from the catalogue were included in the final selection.

That final selection was made by the author of the present article on the basis of patterns emerging from the wider ERNiE study as linked to what was prima facie apparent in Dutch canon discussions and in the DBNL N-gram Viewer. The result of the working selection was as follows:

| Name12 | Period | Field |

|---|---|---|

| Henric van Veldeke | 1000-1450 | literature |

| Jacob van Maerlant | 1000-1450 | literature |

| *Reinaert de Vos | 1000-1450 | literature (fictional character) |

| *Tijl Ulenspiegel | 1000-1450 | literature (fictional character) |

| *Erasmus | 1450-1600 | philosopher |

| *William the Silent | 1450-1600 | statesman, revolt leader |

| *Joost van den Vondel | 1600-1700 | literature |

| Jacob Cats | 1600-1700 | literature |

| P.C. Hooft | 1600-1700 | historian |

| *Rembrandt van Rijn | 1600-1700 | painter |

| Johannes Vermeer | 1600-1700 | painter |

| Johan de Witt | 1600-1700 | statesman |

| *Michiel de Ruyter | 1600-1700 | admiral |

| *Baruch Spinoza | 1600-1700 | philosopher |

| Willem Bilderdijk | 1750-1850 | literature |

| Hendrik Tollens | 1750-1850 | literature |

| Jacob van Lennep | 1800-1900 | literature |

| Nicolaas Beets | 1800-1900 | literature |

| Multatuli | 1800-1900 | literature |

| Louis Couperus | 1850-1920 | literature |

| Guido Gezelle | 1850-1920 | literature |

This is to some extent a preselected list, gravitating (naturally enough, in a library) to the literary and intellectual field. We took care, for reasons of balance, to include some figures from the Dutch National Canon from other fields (political history, painting). After a few trial runs involving a “long-list”, the team decided on a chronological cut-off point of 1914. After that date, the “afterlife” period was too short to generate a meaningful quantity and chronological spread of documentary data. This meant that Anne Frank was excluded, even though her name and her writing make her easily the most important Dutch writer at present. But in the decades in which, in absolute numbers, her afterlife was substantial, those absolute numbers began to count for less and less in the total number of publications per annum lodged in the KB. Anne Frank, and other post-1900 authors, suffered from a generalized decline in the overall salience of canonical authors as such.

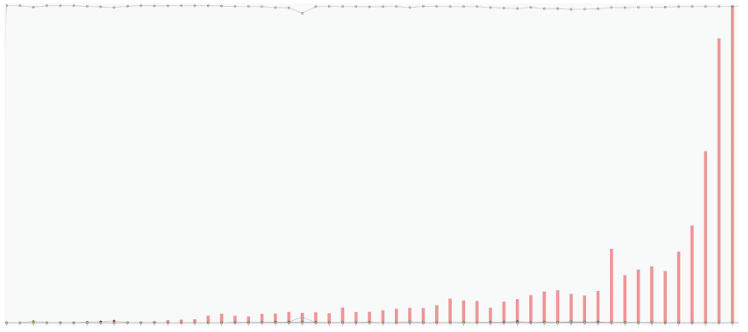

This in itself was an arresting finding. The salience of canonical authors drastically declines after 1900. Until 1900, canonical authors annually account for a substantial portion of the KB’s overall collection intake and are overrepresented in the KB holdings. Towards 2000, their share in the total KB holdings declines and almost flatlines (Figure 6). This is an arresting pattern to emerge from the data, and will be discussed further below. For now, it means that post1900 authors, let alone a post-1945 presence like Anne Frank, for all of her canonical status, is quantitatively swamped.

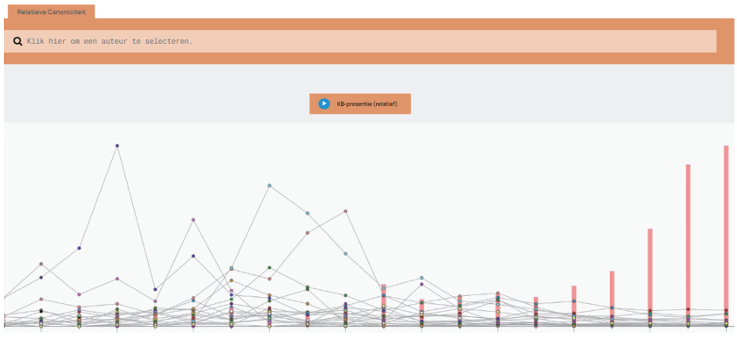

As Figure 4 illustrates, we assessed the quantitative figures in two ways (both accessible at the CanOT (Canonicity over Time) website): in absolute and relative terms. The relative figures factored in the fact that book production in 1950 was many times more voluminous than in 1650, and that the presence of an author or figure at any given time should be adjusted for that proportionality.

Figure 4. Relative presence of canonical figures in relation to the totals in the KB. Interactively accessible at https://lab.kb.nl/tool/canot

The most recent authors that were included were Louis Couperus and Guido Gezelle. Their afterlife too was affected by the 20th-century “canon submergence” phenomenon, but remained a noticeable presence. Gezelle, a foundational literary figure in the Flemish movement, was also included to ensure a post-medieval Flemish presence. Remarkably, the post-1400 figures who qualified for inclusion proved invariably to be from the Hollandish, Protestant heartland of the Netherlands, between Rotterdam and Amsterdam. Among them, the pre-Reformation humanist Erasmus and the Cologne-born Joost van den Vondel are the only Catholics, Baruch Spinoza the only Jew.

Thus even the selection and preparatory management of the data proved to be entangled with more analytical questions regarding the nature of canonicity. The very act of technically setting up this pilot probe turned out to be an intellectual exercise yielding instructive insights. The submergence phenomenon was one of them; and there were other “Canon Quirks”.

Not only does the Dutch canon prove to skew towards the country’s Amsterdam/Rotterdam, Protestant heartland, there is also (as readers will have noticed in the decision not to include the all-too-recent Anne Frank) a glaring absence of women in this list. In the selection preparations we had taken care to include on the “longlist” female authors such as the pre-Reformation poets Hadewych, Anna Bijns and Suster Bertken, and the late-Enlightenment writing duo Elisabeth Wolff and Agatha Deken, all of whom now enjoy a high reputation; but the “hits” these names elicited proved to be insignificant amidst the other ones. This striking mismatch between reputation and actually documented canonicity indicators can partially be explained by their belated rediscovery and appreciation. Hadewych, Bijns and Bertken wrote religious poetry which was only retrieved from oblivion in the later nineteenth century, as their Catholic faith became marginal in a Protestant-dominated country. Their absence from the quantitative data shows how canonicity is fully determined by reception history. Their current rediscovery bespeaks a twofold development affecting that reception history: the declining hold of Protestantism over Dutch culture (although secularization means that their religious poetry has been reframed as generically “spiritual”) and a more women-inclusive historical consciousness.

The apparent disregard for Wolff and Deken is more puzzling. Their main work, the humorous epistolary novel The History of Miss Sara Burgherheart (1782), has long been acknowledged as a masterpiece and enjoys a robust celebrity status within the DBNL, with many reprints and a good deal of critical discussions and appreciation. Outside the literary filiation as attested by the DBNL text corpus, it has failed to generate remediations, adaptations or popularizations, offering a stark contrast to the reception history of Jane Austen in the English-speaking world (more on which below).

More generally, the mismatch between status and popularity for Wolff and Deken may be due to the fact that the eighteenth century in Holland has long been seen as a period of decline after the heroic glory days of the “Golden [seventeenth] Century”. It was deprecated as the “time of the powdered wigs”, when the United Provinces lost their predominance as a colonial world power, arts and letters declined after the heyday of Rembrandt and Vondel, and the country sleepwalked towards the ruination of the Napoleonic period. That was the general view of Dutch history, and it was the nineteenth century which really established the cult of the “Golden Century”, re-canonizing its historical figures (witness the statues to William the Silent, De Ruyter, Vondel, Rembrandt). In this love-in between the nineteenth and the seventeenth century, the great representatives of eighteenth-century Enlightenment literature were squeezed out – as was the third great woman author from that period: Belle van Zuylen (Mme de Charrière).

This very absence of the excluded women, as it troubled our preliminary operationalization of the Dutch case and the management of our relevant data, proved suggestive for the workings of canonicity over time: the seventeenth “golden” century is privileged at the cost of female religious poets of the Middle Ages and Enlightenment novelists, and the nineteenth century was an important filtering amplification platform for those seventeenth-century figures which it recycled and celebrated.

The totality of the KB data cover publications from 1450 onwards, i.e. from the very beginning of print culture. However, the data distribution over that timeline is starkly skewed towards the present, largely because of the enormous increase in book production as a whole (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Totals of canonicity indicators in the KB over time. CanOT-database.

The distortion is twofold. The scant but long-stretched-out productivity pre-1800 dominates the horizontal X-axis (time) and squeezes the data into an undifferentiated explosion as we move towards the present. Conversely, the huge productivity of the most recent decades dominates the vertical Y-axis (publication numbers) and flattens the productivity of the earlier centuries into an insubstantial simmer. This in itself is meaningful. Canonicity as “afterlife” depends on two factors: the duration and sustained permanence of a cultural presence (extreme case: Erasmus with his long X-axis), and its social and quantitative prominence (extreme case: Anne Frank with her tall Y-axis). Remarkably, this twofold skew was only partially obviated when looking at relative rather than absolute figures (cf. Figure 6).

Permanence and prominence appear to be, to some extent, counterbalancing factors: it is hard to combine both; the Bible may be a unique example where permanence and prominence go together. Canonicity moves between heuristic poles: short-lived but widespread popularity (Elvis Presley,13 Game of Thrones) versus long-lived but restricted prestige (Cicero, Augustine). Against this heuristic polarity, remediations proved to be an important mechanism linking the two.

The robust canonicity of Jane Austen combines permanence and prominence, filiation and affiliation; it is expressed, not only by the reprints of her novels and by the biographical and critical studies dedicated to her, but also by the translations, film and television versions (some of them using new settings in contemporary India or California, or involving zombies), by the cosplaying “Janeite” aficionados and re-enactors, and by the publicity surrounding all of those remediations and spin-offs – culminating in the fact that her portrait was placed on an English £10 banknote in 2017. In the libraries, we find her collected works in many reprints, translations and adaptations, documenting the filiative aspect of her afterlife; and also, more indirectly, reflections in printed publications on the popular affiliations wider afield – e.g. Lynch 2000 on the Janeites.

This capacity for cultural products to inspire other cultural productions has been identified by Ann Rigney (2012) as “pro-creativity”: the fact that a cultural creation can “go forth and multiply”. Not merely the product of creativity, it can itself become an agent of inspiration. Crucially, this pro-creativity can move from one cultural medium to others, from opera and film to musicals and graphic novels. This is what is referred to as “remediation” (Erll & Rigney, 2009). Remediation has been interpreted as a manifestation of canonicity. But the contrast between Jane Austen on the one hand and the fallow afterlife of Wolff and Deken, or Belle van Zuylen, suggest that it may be more than that. In sharp contrast to Jane Austen, there have been few Austen-style remediations of Wolff/Deken or Belle van Zuylen, whose lack of wider canonicity stands, as we noted at odds with their high esteem among critics and literary historians. This suggests that intermedial procreativity is a precondition for the successful maintenance of canonicity over time. Culture either swims or sinks. Remediation can transmute the symbolical capital of permanence into the cultural capital of prominence: adaptations in film, music or other media. In the Dutch case, the ongoing actualizations of admiral Michiel de Ruyter are striking: taking the form of statues, postage stamps, banknotes, commemorative events, songs for school children, street names, and an epic-heroic movie.14

Such spin-offs can themselves become “procreative” in their own right, inspiring later superadded spin-offs. Not only are Vondel and Rembrandt canonical figures who gained their fame in the 17th century; the statues that were dedicated to them in the nineteenth century have become cultural icons in their own right, and the Amsterdam Vondelpark and Rembrandtplein are in themselves so well-known that they bolster the recognizability of the dedicatees. Even if those cultural references may not be uppermost in the minds of passersby, an aura of familiarity is sustained by this steady presence in public space, even by the fact that tram and bus stops are named after them and are called out like an endless mantra to the passing passengers. We may call this, in analogy to Michael Billig’s notion of “banal nationalism” (Billig, 1995), “banal canonicity”.

Banal canonicity (street names and other forms of background noise in the public sphere) seem to be the ultimate vanishing point towards which the trajectory of remediation leads. As such, it posed a problem in our data management – or rather, an instructive challenge. Having a central city square or park named after one must constitute the ultimate affiliative accolade, but it also reduces one’s name to a mere bus-stop identifier. What to do with the Leiden Boerhaave hospital, with prestigious cultural prizes named after P.C. Hooft, Erasmus and Spinoza, with an entire university called Erasmus? The KB catalogue includes many publications referring to the Boerhaavekliniek, the Erasmus University or the PC Hooft Prize. Should they be dismissed as mere “false hits”, noise on the line? The dilemma was brought to a fine point by the case of the prominent 17th-century poet Jacob Cats. His name generated a large number of obvious false hits, having to do with the feline animal, the T.S. Eliot poems or the Andrew Lloyd Webber musical based on those poems, or a Volendam pop group called The Cats. All these had, of course, to be filtered out. But what to do with the Cats House, Catshuis? This was originally the estate of the actual poet, and was named after him, but it is now the official residence of the Dutch Prime Minister, and Catshuis is often used to refer metonymically to Dutch government business, like “the White House” or “the Elysée Palace”.15

In any event, we dealt with “banal canonicity” pragmatically. While the phenomenon of banal canonicity should not be disregarded altogether, we did not want it to flood the more specific data. When the name was used merely as a brand, we left the publications carrying that brand out of account (e.g. proceedings of conferences held at the Erasmus University). We did include, however, occasions where the name was deliberately invoked with explicit reference to the historical figure and/or his work, e.g. in the publicity surrounding the rebranding when Rotterdam’s Economic College and Medical Faculty merged into the Erasmus University in 1973.

A final skew factor which had to be taken into account was the aspect of international canonicity. While some figures are known mainly within the Netherlands, others (Erasmus, Spinoza, Rembrandt, Vermeer) enjoy worldwide fame and enjoy an afterlife in other countries and continents. The publications generated internationally (mainly, though not exclusively, academic ones) are also represented in the Royal Library.16 They bespeak a “hypercanonicity” which adds extra resonance to the intra-national status of the figure involved and heightens their prestige as “figures we can be proud of”. National canonicity in the more specific sense of the term can thus be situated between ambient “banal canonicity” and international “hypercanonicity”.

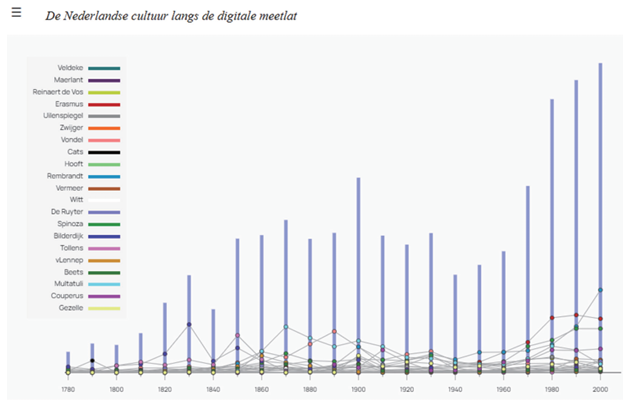

Once the various skews and quirks had been factored into the data analysis, the results were posted online on the interactive CanOT (Canonicity over Time) website, lab.kb.nl/tool/canot. It yielded a timeline-distribution with interesting characteristics (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Canonicity indicators per author (lines) relative to total KB holdings (graphs) per decade. Interactively accessible at CanOT.

Viewed in the entirety of its duration, the time-scale is characterized by low absolute productivity pre-1600. Zooming in on this period (as readers can do interactively on the website) shows a relative prominence of Erasmus. (It may be, of course, that these older items were only acquired by the KB in later centuries, but that bespeaks an acquisition policy which is in itself meaningful.) Zooming in on the period 1600-1700 shows that the most prominent writer was Jacob Cats, challenged but not ousted from the mid-century on by Joost van den Vondel. The main peaks in publication activity are triggered by the prominent and embattled statesman Johan de Witt, murdered by a riotous mob in 1672. At the time he was not yet the lieu de mémoire he would become afterwards, and contemporary interest is mainly political in nature. But curiously, publications about him crest again in 1710, 1725, 1745 and (an explosive peak) 1780. These are intriguing indicators that his afterlife continued to feed into, and was revived by, the faction conflict between parliamentarians and orangists of the subsequent century. I offer this as a suggestion for future historical study.

De Witt apart, the century continues the dual canonicity of Cats and Vondel, but in contrast to the preceding and following centuries, none of the canonical figures is saliently overrepresented. By the end of the century, Cats is the clear leader, despite Vondel’s peaks in 1773, 1779 and 1783. Minor episodic undercurrents of Spinoza are noticeable. From a high-point in 1795 Cats’s productivity plummets to zero by 1800, and from this moment on, the reputation of Vondel is unchallenged.

Around 1820, productivity of canonicity indicators begins to show a marked increase, which rises steeply across the following century. There is another tipping point: from the emergence of Bilderdijk and Tollens in 1810 on, many canonical figures are overrepresented in the KB holdings. Clearly, the nineteenth century is one where the KB acquisitions were dominated by the country’s canonical figures (cf. Figure 4 above).

Viewed in absolute figures, the period 1800-2000 as a whole presents (Figure 7) the “suspension bridge” profile already visible in Figure 2.

Figure 7. Canonicity indicators in the KB catalogue, 1800-2000 (absolute figures). Interactively accessible at CanOT.

While Cats has dropped from sight, Vondel remains in evidence, certainly around the commemorative years of 1867 and 1879, with peaks around 1890, when he even challenges the late-century dominance of Multatuli (peaking in 1875 and 1888). The early part of the century is dominated by Bilderdijk and Tollens, two poets whose canonicity plummets to near-zero after 1860. Bilderdijk holds his own in a minor way alongside presences like Rembrandt (peak in 1852), Spinoza (minor peaks in 1871, 1877), Jacob van Lennep and Maerlant. Erasmus is an altogether minor presence, despite small peaks in 1780 and 1872. The status of Henric van Veldeke, now celebrated as the first named poet in the Dutch tradition, is almost nil – caused, no doubt, by the fact that his signature Servatius poem was not discovered until the late 1850s; he shares the fate of Hadewych.

The turn of the century witnesses a reduced productivity: Canonicity markers now descend under the horizon of the annual publications average. The period is marked by the appearance of Guido Gezelle (1904) and Bilderdijk, Vondel and De Ruyter revivals in 1906-07; the steady consolidation of Reinaert de Vos as a minor presence in the canon – a medieval text which was highly amenable to popularizations, remediations and affiliations (van Oostrom, 2023). Louis Couperus is prominent during the first quarter of the century, flanked by Gezelle, whose presence spikes in 1930 and once again, belatedly, in 1980; Couperus himself profited from TV adaptations of his novels, experiencing minor revivals in 1987 and 2004, and 2013. During the 1930s, interest in Spinoza, Rembrandt and Erasmus becomes more noticeable before the production as a whole slumps to a low ebb in the 1940s.

Postwar, Rembrandt peaks in 1958 and again in 1968, 1991 and hugely so in 2006. 1986 also marks a peak in interest in Erasmus (repeated in 1993), and the beginning of a minor Multatuli revival. The 1990s witness a growing interest in Vermeer, but 1996 is the only year in which his presence is more pronounced than Rembrandt’s. Productivity around the twenty chosen iconcases increases sharply as a whole after 1977; but the decade around 2000 is firmly dominated by the quadriga of Rembrandt, Erasmus, Spinoza and De Ruyter. All of these, remarkably, were depicted on high-denomination banknotes in the preceding decades; the only ones, with Vondel, to have been given that honour from within our selection. There is a minor presence for Vermeer and Couperus. By 2000 Vondel’s tenacious canonicity seems finally to have petered out (also in the curve of his mentions in the DBNL).

Both in the DBNL mentions and in the KB holdings, the long dominance of major seventeenthcentury figures is remarkable. The early- to mid-nineteenth-century cohort failed to appeal to post-1918 culture; only Multatuli and, to a lesser degree, Couperus and Gezelle continued to maintain their cultural presence.

Fully exploring the meaning of the data mapped and charted here would go beyond the scope of an article. A few points can, however, be made.

There are a few obvious inflection points in the historical dynamics of canonicity. One obvious tipping point is the decade around 1800 (what Reinhard Koselleck (1988) calls the Sattelzeit or watershed moment, cf. Motzkin, 2005). The mid-twentieth-century slump reflecting the Second World War is noticeable, but appears to affect the productivity as a whole rather than the relative prominence of this or that figure within the canon. The huge productivity increase of the late 1970s is accompanied, curiously, by a reduction of the palette of canonical figures to a restricted few “hypercanonical” ones.

The conjunctural curves of canonicity for individual authors tend to show a fits-and-starts pattern; we may assume that these mark a pulsation of renewed attention after a period of comparative neglect. Commemorative jubilees or exhibition events may be a factor driving that periodicity (Leerssen & Rigney, 2015).

The tenacity of a “Golden-Century”-centred cohort of hypercanonical figures is remarkable. All of these seem to have received a fresh impetus in their afterlives as a result of national historicism in the nineteenth century; but the nineteenth-century authors involved in that Golden-Age-revival (like Hendrik Tollens and Jacob van Lennep) have themselves all been, by and large, forgotten, their canonicity failing to outlast the 1920s, and the century as a whole falling into the same sort of opprobrium (dull, stagnant) which it had heaped on the eighteenth. And so the Golden Century abides, accompanied by a flanking cohort of figures from the shifting present, whose canonicity is measured in decades rather than centuries.

It may well be that this pattern will be disrupted by the recent, powerful tendency to turn away from Dead White Males and to focus instead on the under-represented identities in Dutch culture. With her Digitaal Vrouwenlexicon van Nederland (resources.huygens.knaw.nl/ vrouwenlexicon/), Els Kloek has given a solid basis for a more women-inclusive re-calibration of history. The inclusion of the great Suriname-born anticolonial author André de Kom in the 2020 Canon van de Nederlandse Geschiedenis, and of Tula (the heroic insurgency leader of enslaved plantation workers in the colonial Antilles) as the national hero of Curaçao, are noteworthy. How and if this contemporary trend will actually subvert and dislodge the centuries-long weight of the national canonicity of the Golden Century is an open question. The continuing dominance of the hypercanonical quadriga in the opening decades of the 21st century stands at odds with feisty proclamations like the one at the “Canon Festival” website of the Netherlandic Taalunie: “Max Havelaar [by Multatuli, JL] and Reynaerd are the outstanding Netherlandic classics; female authors are strongly on the rise”.17 That impression tallies more with the popularity curves as registered in the DBNL N-gram Viewer (i.e., from within the filiative intertextual presence amongst persons actively involved with literary pursuits); these remain fairly constant in the period 1900-2000, in contrast to the flatlining curves as evidenced in the KB holdings.

The implication is twofold. Firstly, canon formation and canon discussions take place within an interest community of those who are actively productive in the literary and/or historical fields. This filiative afterlife diverges from the wider affiliative afterlife, where “banal canonicity” seems to count for more – tellingly, the KB’s hypercanonical quadriga also happen to be featured on banknotes and are overrepresented on postage stamps, street names and in remediations, in contrast to DBNL favourites. Secondly, contemporary canons are hodiecentric and overestimate their own filiative engagement with past masters. Impelled by their contemporary topicality, they tend to be relatively oblivious to their own position in the long history of cultural affiliation. One thing we may surmise is that for figures to gain and maintain canonicity, an element of procreative remediation is crucial: the capacity to gain fresh media of representation and adaptation. Anne Frank’s reputation, like that of Reynard the Fox, can profit from that effect, while a lack of it has hampered the canonicity of Belle van Zuylen and of Wolff and Deken. We may predict that this remediative aptitude will play an important role in the further afterlife of whatever new presences are entering new canons. Also, new, non-print media appear to be crucially important: the submergence effect (noted earlier on as a dominant factor in the later twentieth-century) tallies with the fact that maybe libraries are losing their status as reliably representative reservoirs of canonicity indicators.

That last observation places the fundamental working assumptions of this article in the crosshairs. Canonicity until 1950 could be confidently expected to be reflected in the holdings of a national copyright library like the KB. In recent decades, the remediation of canonical figures into new, non-print platforms of leisure-time mass consumer culture (musicals, drama series on TV and streaming media, tourism, social media) has become much more pronounced. Here, too, this highly salient contemporary presence may be counterbalanced by a lack of long-term permanence; but it does mean that for Anne Frank, we missed out on a good deal of canonicity markers simply because they were not deposited in the KB, or only registered to the extent that they triggered print-media reflections.

That is a cause for modesty. This article has not measured canonicity as such, but canonicity as indicated within our chosen dataset and working field; but then again, that crux affects all empirical research. As it is, the findings – and the experiment of setting up the study itself, as a “proof of concept” – did suffice to raise suggestive questions about many assumptions hitherto insufficiently addressed in canonicity debates:

These stand, not so much as firm conclusions, but as “sightlines”: strongly suggested research hypotheses for future work on the topic.

One thing that became clear as I prepared and evaluated this pilot study is certainly how the ongoing praxis of canon generation and canon debates is marked by a lack of historical reflection on the transience of its own endeavours. Canon-builders sit in judgement over the past but gain their authority to do so purely from the momentary cultural constellation of the fleeting present. They show little reflection on the fact that theirs is an iterative historicist praxis which is rooted, and was demonstrably paramount, in the nineteenth century – that period when all the statues were put up, and when (as we can see from the salient overrepresentation of canonicity-indicators in the KB for those decades) the canon was important. The flatlining of canonicity-curves, submerged in the later twentieth century (Figures 4 and 6) raises doubts whether that importance is still there. Maybe library-trained and library-oriented intellectuals (like the author of this article, or all those critics and academics who have over the last decades dealt with canonicity) are continuing a nineteenth-century habit in a post-2000 world.

On the other hand, however, the canon-critical, inclusivity-oriented trend of recent decades and the turn away from print culture will have to contend with a very deeply-ingrained inertia in the canon as such: the self-perpetuating marketability of celebrity, the need for cultural literacy, the tendency to see a canon as something that links the aspirational collectivity of nation (as opposed to society‘s dividedness) to its collective past. This national gravitation in the canon seems to me as deeply ingrained as its historicism and its axiological embeddedness in value judgements; and the nation is as potent a political force now as it was in 1870 or 1910.

With thanks to Juliette Lonij, Pim van Bree and Geert Kessels, Susan Legêne, and Ann Rigney. I am also grateful to the Royal Netherlands Library for granting me a research fellowship in 2018 (through the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Studies, NIAS), which enabled me to set up the research project covered in this article.

1 In a lecture held in Warsaw in 1935, quoted by Knuvelder (1978), my translation. I have rendered Ingarden’s Konkretisierung as “reading’: how a text as an abstract, encoded object is turned into an actual, concrete experience by virtue of being read.

2 The list is online and can be studied interactively at http://e-rn.ie/iconicindividuals. Clicking any name will bring up an item view with tabs linking to the various representations in writing, monuments, paintings, stamps/banknotes, musical life or films. A sociogram of their media presence and social position is interactively accessible and further explained at https://e-rn.ie/memorynetwork.

3 These twin concepts I take from Edward Said (1983), 29-30, cf. Di Leo (1999).

4 An interesting study of canon formation in the pre-1800 Low Countries in Van Deinsen (2022).

5 Generally: Assmann and Czaplicka (1995); Erll & Rigney (2009); Rigney (2012).

6 The modernization of “communities” towards “societies” follows the old opposition of Gemeinschaft vs. Gesellschaft of Ferdinand Tönnies (Tönnies, 1979), and accompanied by what Habermas (1962) has called the structural shift of the public sphere. For a closer discussion, see Leerssen (2023). Said (1983) sees a similar dynamic between filiation and affiliation.

7 For the importance of the Norton, Oxford and Palgrave Anthologies in the Englishspeaking world, see Leerssen 2020; also Price 2000. Reich-Ranicki’s canon-building-cum-anthologizing was anticipated in the Netherlands by the anthologies of the prominent poet/critic Gerrit Komrij (1979, 1986). Komrij’s own authoritativeness was underscored by the award of the prestigious PC-Hooft-award in 1993 and the status of ‘Poet of the Nation’ (Dichter des Vaderlands) in 2000.

8 In the Netherlands, the 2006 canon served as the template for a National History Museum proposed on the initiative of two politicians from the Christian-Democratic and the Socialist parties, with the avowed aim to bring society together around a shared set of narratives. The museum remained unrealized but a permanent exposition visualizing the canon was installed in the Netherlands Open Air Museum in 2017.

9 As Itmar Even-Zohar (1990) has pointed out, the complex interactions of taste and reception dynamics play out, not in a single, undifferentiated and homogenous historical space, but in a complex and interlocking ‘polysystem’. Different genres (science fiction, women’s literature, migrant literature, children’s literature, coming-of-age novels, magical realism etc.) each have their canons and intersect mutually (women’s migrant literature, youngadult science fiction) while they are situated within, or form conduits between, the partoverlapping canons of different countries (Ireland, Nigeria, Argentina, Spain, Netherlands) or language communities (English-language, Spanish-language, Netherlandic-language). In other words, the idea of a canon, while evoking historical permanence, involves dizzyingly dynamic interactions and transfers – beside being drastically changeable over time. That, amidst all these competing frames of canonicity, the national one should be paramount, accords with the observations of Max Weber and Karl Deutsch to the effect that in the twentieth century the nation trumps all other frames of identification (religion, class etc.).

10 These terms and indeed the approach were inspired by the then-popular bibliometrical approach used to establish the importance of authors and journals. Bibliometric measurements are not without problematics of their own: Garfield 1999, Larivière & Sugimoto 2019, Taber 2005, Woeginger 2008. Awareness of this was taken on board also in the selection and evaluation of the KB data, as discussed below.

11 The interactive DBNL N-gram Viewer, conceived by Els Stronks, is accessible at https:// www.dbnl.org/ngram-viewer/.

12 Names marked with an asterisk showed up in the ERNiE list of national icons as discussed above.

13 I include his name partly as homage to the inspiring album title 50,000,000 Elvis Fans Can’t Be Wrong (1959)

14 https://ernie.uva.nl/viewer.p/21/56/object/131-137013

15 That case of “banal canonicity” involves an element of actual filiation: the poet Cats had left his name behind in his residence – comparable to the Anne Frank House being named after the diarist. This is qualitatively different from an association-by-affiliation: the retroactive dedicatory invocation, as with the Vondelpark or the P.C.Hooft-street. This in turn invites us to inquire further into the specifics of affiliation. The framework for these is usually national: most Dutch cultural prizes are named after Dutch canonical figures. More specifically, the affiliation is local as well as national: the Erasmus University is located in the humanist’s home city of Rotterdam, Vondel, Rembrandt and PC Hooft were figures in, specifically, Amsterdam city culture. The multiscalarity, interdependence and interpenetration of local and national frames of cultural affiliation pose an intriguing question for future research.

16 How the KB has gathered national and international materials can be seen interactively online at https://nlcldm.nodegoat.net/viewer.p/44/1057/scenario/4/geo/. The KB holdings connect places of publication in the Netherlands (with a subsidiary cluster in Belgium) to the extent that the connecting lines almost draw an outline of the Netherlands as a country, much as the distribution of statues did in Figure 2 (the zoom function in the visualization allows users to spot this pattern). In addition, transnational lines reach out to places of work and publication abroad, with important foreign hubs in Berlin, Paris, London and New York (in order of emergence). In establishing a national canonicity, these international instances can be to some extent discarded – but not altogether.

17 “Max Havelaar en Reynaert zijn dé Nederlandstalige literaire klassieken; vrouwelijke auteurs zijn in opmars”, “Canon Festival” website, https://taalunie.org/actueel/324/ resultaten-nederlandstalige-literaire-canon-bekendgemaakt, posted 1 October 2022, consulted 14 August 2024.

Abbeloos, J.-F. (2023, January 7). Het subsidieverhaal van Vlaanderen. De Standaard. https:// www.standaard.be/cnt/dmf20230106_97983001

Assmann, J., & Czaplicka, J. (1995). Collective memory and cultural identity. New German Critique, 65, 25–133.

Billig, M. (1995). Banal nationalism. Verso.

Bloom, H. (1994). The Western Canon: The books and schools of the ages. Harcourt Brace.

Brillenburg Wurth, K., & Rigney, A. (Eds.). (2011). Het leven van teksten: Een inleiding tot de literatuurwetenschap. Amsterdam University Press.

Cruse, I. (2011). Library Note for the House of Lords debate on 20 October 2011: “Teaching History in Schools”. Westminster: House of Lords. https://www.parliament.uk/globalassets/ documents/lords-library/Library-Notes/2011/LLN-2011-030-TeachingHistorySchoolsFP2. pdf

van Deinsen, L. (2022). Literaire erflaters: Canonvorming in tijden van culturele crisis, 1700-1750. Verloren.

van Deinsen, L., Sevenants, A., van de Velde, F., & Vertommen, G. (2022). De Nederlandstalige literaire canon(s) anno 2022: Een enquête naar de literaire klassieken. KANTL.

Di Leo, J. R. (1999). On being and becoming affiliated. Symplokē, 7(1/2), 49–63; also in J. R. Di Leo (Ed.), Affiliation: Identity in academic culture, (pp. 101–114). University of Nebraska Press.

Duyvendak, L., & Pieterse, S. (2009). Van spiegels en vensters: De literaire canon in Nederland. Uitgeverij Verloren.

Erll, A., & Rigney, A. (Eds.). (2009). Mediation, remediation, and the dynamics of cultural memory. De Gruyter.

Even-Zohar, I. (1990). Polysystem theory. Poetics Today, 11(1) (special issue on Polysystem Studies), 9–26.

Garfield, E. (1999). Journal impact factor: A brief review. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 161(8), 979–980.

Grever, M., Jonker, E., Ribbens, K., & Stuurman, S. (2006). Controverses rond de canon. Van Gorcum.

Guillory, J. (1993). Cultural capital: The problem of literary canon formation. University of Chicago Press.

Habermas, J. (1962). Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit. Luchterhand.

Hobsbawn, E., & Ranger, T. (Eds.). (1983). The invention of tradition. Cambridge University Press.

Knuvelder, G. (1978). Ingarden en de receptietheorie. Spiegel der Letteren, 20, 67–68. https:// www.dbnl.org/tekst/_spi007197801_01/_spi007197801_01_0004.php

Komrij, G. (Ed.). (1979). De Nederlandse poëzie van de 19de en 20ste eeuw in 1000 en enige gedichten. Prometheus.

Komrij, G. (Ed.). (1986). De Nederlandse poëzie van de 17de en 18de eeuw in 1000 en enige gedichten. Prometheus.

Koselleck, R. (1988). Vergangene Zukunft: Zur Semantik geschichtlicher Zeiten. Suhrkamp.

Larivière, V., & Sugimoto, C. R. (2019). The Journal Impact Factor: A brief history, critique, and discussion of adverse effects. In W. Glänzel et al. (Eds.), Springer Handbook of Science and Technology Indicators (pp. 3–24). Springer.

Lavèn, A. (2020, June 22). Nieuwe Canon oogt evenwichtig, maar soms geforceerd. Historisch Nieuwsblad. https://www.historischnieuwsblad.nl/nieuwe-canon-oogt-evenwichtigmaar-soms-geforceerd/

Leerssen, J., & Rigney, A. (Eds.). (2015). Commemorating writers in nineteenth-century Europe: Nation-building and centenary fever. Palgrave.

Leerssen, J., van Baal, A. H., Rock, J. (Eds.). (2022). Encyclopedia of Romantic Nationalism in Europe (2nd ed.). Amsterdam University Press. http://ernie.uva.nl

Leerssen, J. (2020). Digesting the past: Anthologies and bicultural memory in Ireland. In J. Leerssen (Ed.), Parnell and his times, (pp. 123–147). Cambridge University Press.

Leerssen, J. (2023). Heart to heart: The power of lyrical bonding in romantic nationalism, Interlitteraria, 28(1), 8–19.

Lynch, D. (Ed.). (2000). Janeites: Austen’s disciples and devotees. Princeton University Press.

Motzkin, G. (2005). On the notion of historical (dis)continuity: Reinhart Koselleck’s construction of the «Sattelzeit». Contributions to the History of Concepts, 1(2), 145–158.

Nora, P. (1997). Entre Histoire et Mémoire. In P. Nora (Ed.), Les lieux de mémoire (Quarto ed., Vol. 1, pp. 10–50). Gallimard.

van Oostrom, F. (2007). Een zaak van alleman: Over de canon, schoolboeken, docenten en algemene ontwikkeling. Amsterdam University Press.

van Oostrom, F. (2023). De Reynaert: Leven met een middeleeuws meesterwerk. Prometheus.

Price, L. (2000). The anthology and the rise of the novel: From Richardson to George Eliot. Cambridge University Press.

Rigney, A, (2012). The afterlives of Walter Scott: Memory on the move. Oxford University Press.

Reich-Ranicki, M. (2006). Der Kanon: Die deutsche Literatur (5 vols.). Insel.

Said, E. (1983). The world, the text, and the critic. Harvard University Press.

Smets, W., Tuithof, H., & de Groot-Reuvekamp, M. (2023). Wat is de meerwaarde van een canon voor het geschiedenisonderwijs? Een didactische reflectie op het canondebat in Vlaanderen. Tijdschrift Voor Geschiedenis, 136(2), 159–167. https://doi.org/10.5117/ TvG2023.2.005.SMET

Taber, D. F. (2005). Quantifying Publication Impact. Science, 309(5744), 2166a. https://doi. org/10.1126/science.309.5744.2166a

Tönnies, F. (1979). Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft: Grundbegriffe der reinen Soziologie (3rd ed.). Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Tollebeek, J., Boone, M., & van Nieuwenhuyse, K. (2022). Een canon van Vlaanderen: Motieven en bezwaren. KVAB.

de Vos, M. (2009). The return of the canon: Transforming Dutch history teaching. History Workshop Journal, 67, 111–124.

Woeginger, G. J. (2008). An axiomatic characterization of the Hirsch-index. Mathematical Social Sciences, 56(2), 224–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mathsocsci.2008.03.001

van der Woud, A. (1998). De Bataafse hut: Denken over het oudste Nederland, 1750-1850 (2nd ed.). Contact.

Zerubavel, E. (1996). Social memories: Steps to a sociology of the past. Qualitative sociology, 19, 283–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02393273